With the changing of the seasons I’ve been doing a lot of reflection. This summer, Rob and I spent a lot of time alpine climbing, which got me thinking about the gear I used – what worked, what didn’t, and why. The first piece of gear that came to mind is my Black Diamond Speed 22 pack! This pack makes me really happy when I’m using it – yes, I said that about a backpack. Hehe 😀 If a piece of gear can bring me this much joy, I guess it’s worth writing about! But first, let me start by defining what I mean by an “alpine climbing pack.” When I use this term I am referring to a pack worn when rock climbing in the alpine. Straight forward, right? This pack is for day missions that could be more committing, thus needs to be large enough to carrying all my extra layers, water, food, first aid, etc. as well as an ice axe and crampons if they are needed, yet it needs to be small enough so as not to interfere with my rock climbing performance. I think a pack in the 20-25L range for capacity is perfect – my pack is a size small/medium so it’s actually 20L. I’m also referring to a pack that can fit inside my overnight pack when I’m on a multi-day trip, as this is the system like to use – I prefer packs with solid hip belts for carrying heavy loads but these don’t climb well so I bring two packs. Unfortunately, since I have BD Speed 22 in size small/medium (I’m 5’1″ by the way), which they no longer make, once I wear it out I’m going to need to find something else. Ugh. Thus on top of talking about my favourite pack and why it’s my favourite, I thought this would be a good excuse to talk about these types of packs in general and take a look at the other options out there. Being a “petite alpinist” (haha that sounds funny 😜) however, I know finding something in the right size is going to be the biggest challenge, let alone have all the features I’m looking for.

So how do I pack for an alpine climb? Well, that’s a great question – I’m glad you asked! 😉

I’ll start by talking about what I pack and how I pack, so you can think about how it relates to your system and thus judge how relevant some of my comments are to you. I like having a combination of items in my pack as well as on my harness. This distributes the weight between my pack and harness – women have a lower centre of gravity so we’re designed more so to carry loads on our hips compared to men. This also means I can get by with a smaller capacity pack, which I find is better for rock climbing. With this in mind, I leave camp or the car with my harness on with my climbing gear and climbing shoes on my harness. I also prefer leaving like this so all I need to do when we get to a climb is flake the rope, have a quick snack, put on some sunscreen, and change my shoes. If I am on a more committing alpine route here is an example of what I’ll likely have inside my pack:

- Waterproof jacket and pants

- Small micro insulated jacket – this type of jacket is great when I need an insulating layer while climbing but don’t want to overheat. I can also clip it to my harness.

- Medium insulated jacket – when paired with the above jacket is good if we are benighted.

- I may have another thin long-sleeve layer in there, it depends on the weather that day – I could be wearing it instead (I always wear at least a pair of climbing pants and a t-shirt while climbing)

- Merino toque – that fits well under my helmet

- A buff

- Sun hat

- Gloves – sometimes a second pair if I think they’ll get wet

- SOL bivy

- First aid kit

- Personal locator beacon

- 2L water bladder with water 🙂

- Lots of food

- Sunglasses with a case

- Headlamp

- Spare batteries

- Small container of sunscreen and SPF lip balm

- Helmet

- Rope – coiled and strapped under the lid for the approach

- Crampons (if necessary)

- Ice axe (if necessary)

- Note: I have been able to fit my mountaineering boots (LaSportiva Trangos size 37.5) inside my pack during a climb if needed but for many people this may be difficult with 20L. I think for people with larger feet 25-30L be better.

I think that’s everything!

Alright, let’s break down the important features of an alpine climbing pack.

Features of the BD Speed 22 that I like and use as a benchmark for other packs:

- A strap under the lid to attach a coiled rope – adds stability/security.

- Top-loading – I’ve seen some designs that still have a strap to hold a rope even though they don’t have a lid, and they seem to work well but I find I prefer the lid because it’s usually bigger than any external pockets on those other packs. The lid of the BD Speed 22 is large enough to fit all the things I need easy access to regularly.

- A floating lid that can be adjusted in the front and back – a long front attachment means the lid won’t flap around when the bag isn’t full and adjustable back straps are great for giving more space when the pack is full but you still need to attach the rope.

- Under the lid storage pocket is nice.

- Capacity of 20L – I think this is the perfect capacity but for taller individuals a 25-30L pack might be necessary. Rob, who is 5’9″, uses a 30L pack but there is always extra space in his pack.

- Smaller size – The S/M fits me perfectly – the shoulder straps aren’t pulled all the way down, there isn’t lots of extra webbing dangling when I do up all the straps, and even when full, the pack is still high enough above my harness/chalk bag that I can chalk up just as a would if I wasn’t wearing this pack (I find with packs that don’t fit I have to push it out-of-the-way when I want to chalk up). The streamlined design helps in this regard as well.

- Two ice axe holders

- Compression straps – great to eliminate extra space when the pack isn’t full and to still provide support to a rope if carrying a rope on the outside and the pack isn’t full.

- 2L water bladder sleeve

- Durable shoulder straps – I find the mesh kind are not strong enough.

- The shoulder straps are positioned high enough/the lid is low profile so that when I look up the pack isn’t in the way.

- Only webbing for the “hip belt“

- A somewhat stiff back panel for support when the pack is full and so the bag won’t buckle when not full (though the buckle usually only happens when a bag doesn’t fit).

- This pack is made out of a durable nylon material, so the focus is on the durability rather than being lightweight, which I prefer.

- A durable handle so I can dangle the pack from my belay loop while in a chimney and know it won’t break.

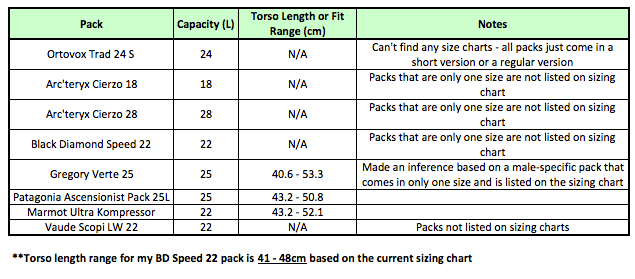

So my online research on other alpine climbing packs turned up lots of great packs but only one in the <30L capacity range that came in a size “short” – all other packs came in only one size (which has always meant they won’t fit)! This pack was the Ortovox Trad 24 S. There’s no size chart associated with this pack however, so I’m assuming that since it is labelled as a “short” version that it would work for me. In general, it was difficult to find torso length ranges for these packs that only come in one size – they were often not listed on the size charts. In any case, here are some packs that I think are still worth checking out for those of you who are not as vertically challenged as I am. 🙂 These packs don’t necessarily have all the features I mentioned above and I haven’t checked them out in person, but I think they still have a lot of the really important features and are worth considering:

- Arc’teryx Cierzo 18 or Arc’teryx Cierzo 28

- Black Diamond Speed 22

- Gregory Verte 25

- Patagonia Ascensionist Pack 25L

- Marmot Ultra Kompressor

- Vaude Scopi LW 22

While I was trying to find the torso length ranges for these packs I was going a little cross-eyed, so I opened up Excel…😜 haha! For your reference:

Although, in theory, the torso length range of some of these packs does overlap with the range of my current pack, I’m not too optimistic it would work since it hasn’t before. Next step would be to actually measure my torso, measure the packs, and try them all on in person…haha! Perhaps another time. 🙂 For now, hopefully this post just gives you some food for thought.

I think I’ve rambled for long enough! What’s your favourite alpine climbing pack and why? Add a comment below!

And don’t forget to…

Keep on rockin’ 🗻

J.